Milgram’s obedience studies are amongst the most famous in all of psychology and taught to all psychology students. But if you think you know all about them, chances are that a new film from shortcuts tv, Beyond Milgram, will get you thinking again.

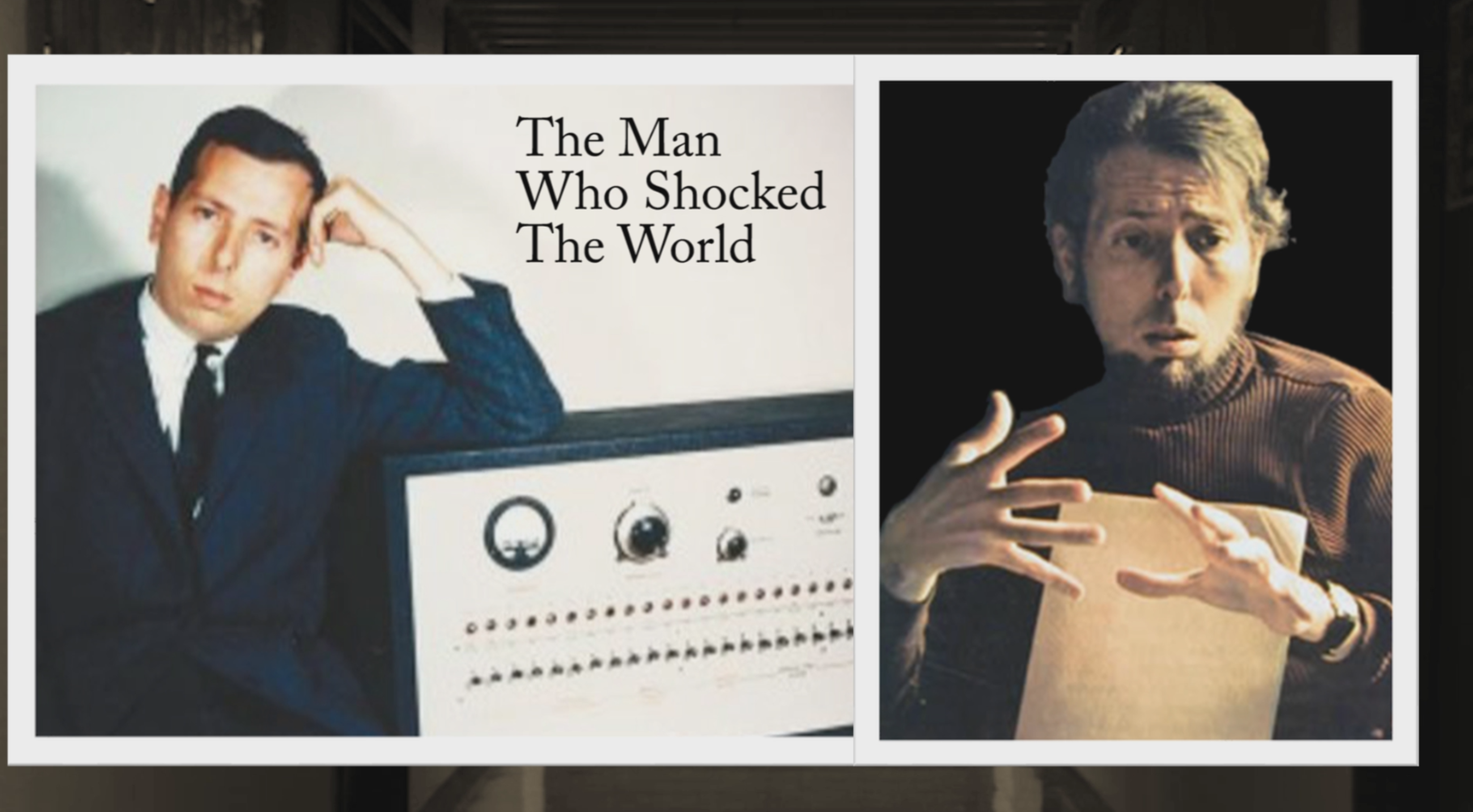

When Professors Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher asked samples of psychology students what Milgram’s experiments showed, over 90% replied that ‘people will obey instructions from someone in authority, even if it means harming others’. This is hardly surprising as the conventional view of Milgram’s shock machine experiments, taught to generations of psychology students over more than five decades, is that they demonstrated that quite ordinary, decent people are capable of inflicting what they believed was serious harm to another person just because they are told to by an authority figure. Some of Milgram’s results were indeed literally shocking. In the famous baseline condition – the one everyone sees with unhappy volunteer ‘teachers’ being told by a white coated experimenter ‘please continue’ giving electric shocks to a complaining ‘learner’ – an incredible 65% of participants continued increasing voltage right through to the maximum 450 volts.

Haslam and Reicher don’t question the validity of Milgram’s findings, nor do they try to explain them away as many have done. On the contrary, they see them as very significant, but argue that the famous baseline condition only tells part of a bigger story. If you look at the many much less familiar variants Milgram used, involving in all almost a thousand participants, you find as much disobedience as obedience and, ironically, when experimenters actually issued the command, ‘You have no other choice, you must go on’, all participants refused to continue.

‘Whatever else these studies are about, and whatever else they show,’ says Reicher, ‘they don’t show that people automatically obey orders.’

Reicher argues that Milgram’s explanation, that people go into a passive ‘agentic state’ where they simply obey orders, just doesn’t fit his own findings! If you listen carefully to the experiments (shown in the film with illustrative clips of the original black and white footage) you see that participants are not passively listening to one voice. Rather they’re actively listening to two voices, the experimenter telling them to continue and the ‘learner’ pleading with them to stop. So the key question here is, why did participants sometimes obey the voice telling them to continue and sometimes refuse?

For Haslam and Reicher, the answer to this question is found in social identity. The famous baseline condition with its incredible rate of compliance was structured to encourage the participants’ identification with the project. It was conducted at the prestigious Yale University, the white coated experimenter was authoritative and also took time to explain to each participant just how important this scientific experiment was for helping to improve learning. However, when Milgram switched the location of the experiments to seedy downtown Bridgeport, compliance fell below 50%. When the experimenters were indifferent, offhand, or simply phoned in commands, compliance fell to just above 20%, and when there were two experimenters who argued with each other and issued contradictory orders it fell to zero.

‘The crucial variable here is identification, says Haslam. ‘People will only obey orders to harm others when they identify with those orders and believe the good outweighs the harm. In Milgram’s experiments, participants obeyed when they believed the good of the scientific cause outweighs the harm being done.’ And when participants were debriefed and told the real purpose of the experiments, most were glad they participated and very few had any regrets about their involvement in spite of the deception involved.

So, according to Haslam and Reicher, Milgram’s experiments are actually telling us a very different story from the one that has been told generations of psychology students and which appears to lend credibility to Hannah Arendt’s notion of the ‘banality of evil’. People obey orders to harm others not because they go into an agentic state that blinds them to the consequences of their actions, but rather because they believe in and identify with what they are doing. This interpretation has massive social implications.

From the point of view of social identity theory, those who organised the mass destruction of populations, planted bombs in city centres, tortured suspected terrorists or gave electric shocks in a Yale laboratory more than half a century ago all shared one thing in common. They identified with what they were doing, in spite of the harm caused to others. They didn’t lapse into a passive agentic state. Rather, they believed that what they were doing was right. And that’s the really frightening thing about Milgram’s experiments.

Steve Taylor has degrees in sociology, psychology and law. He works at the University of London and is a scriptwriter for shortcuts tv.

The full Milgram: Obedience and Identity film is available from shortcuts tv.