The lasting popularity of Arthur Miller’s plays is undeniable. As I write this, there are two Miller productions in the West End: ‘The Price’ (1968) and ‘The American Clock’ (1980). Upcoming productions include the hotly anticipated ‘All My Sons’ (1947) starring Sally Field at the Old Vic and ‘Death of a Salesman’ (1949) at the Young Vic with Wendell Pierce in the leading role. Also scheduled is an innovative female-led production of ‘The Crucible’(1953) at the Yard Theatre in London. Last year, Don Warrington played Willy Loman in an acclaimed production of ‘Death of a Salesman’ in Manchester, while 2016 saw a starry cast including Ben Whishaw, Sophie Okonedo and Saoirse Ronan in an updated setting of ‘The Crucible’ on Broadway. Miller continues to excite actors, directors and audiences with his ability to tackle big ideas and deep emotions, which resonate with different generations around the world. Yet, his work can be challenging to convey in a classroom, with students struggling with the context, often finding the characters’ lives too far removed from their own.

Miller and Time

When Miller’s plays received their first performances, his audience was aware of two time periods, the time in which the play was set and that in which it was written. For ‘The Crucible,’ there was a gap of well over two hundred years between the play’s setting in 1692 Colonial America and being written in the 1950s. However, for a modern audience, there is a third time period to consider: the period in which they are viewing the play. The original audience for ‘The Crucible’ would have known the current events Miller was criticising, whereas a 21st century audience might be entirely unaware of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings. Students today could find both the concerns of the committee, with its hunt for Communists and ‘red’ propaganda, as alien as the lives of the Puritans portrayed in ‘The Crucible’, Below are strategies for making the contexts clear and engaging for students.

Exploring the Salem context:

- Visit the Salem Witch Trials online documentary archive and transcription project (http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/home.html.) There are many fascinating documents including the original accusations of the historic Abigail against John Proctor. Note how Miller’s dialogue was influenced by the language in the transcripts.

- Read and discuss the poem ‘Half-hanged Mary’ by Margaret Atwood about a distant relation of Atwood’s in the 1680s who survived being hung after accusations of being a witch. Consider her status as an outsider and unconventional woman.

- Visit the New England Historical Society website to read about life in Puritan times. Also research the 1676 case of Hannah Lynam who broke the clothing laws, by wearing a silken hood, an useful example of the restrictions placed on young girls.

Exploring HUAC and 1950s America:

- Read excerpts from the play ‘Are You Now or Have You Ever Been’ by Eric Bentley, a piece of verbatim theatre based transcripts from the HUAC hearings. Particularly relevant testimonies include those of Larry Parks, who was emotionally torn by the pressure to confess in order to save his acting career; Elia Kazan, Arthur Miller’s frequent director, who decided to name members of the Communist party; and Miller himself, who did not, saying, ‘’All I can say, sir, is that my conscience will not permit me to use the name of another person.’ There are also some online videos of some of the actual filmed testimonies.

- Read Section 5 of Miller’s autobiography Timebends, which discusses his disappointment in Kazan’s decision to testify, his own inner turmoil and his research of the Salem Witch Trials.

Relevance to the present day

Rather than a series of dates and facts, any research should enhance the students’ understanding of the play and its characters, The following activities and discussion topics could assist with this:

- Study production photos of ‘The Crucible’, including any that are non-traditional, such as the 2016 Broadway production. Ask the students to make a list of the advantages and disadvantages of changing the setting of the play. Have them suggest at least one alternative setting for the play which they think would add to its relevance for a modern audience.

- Discuss the idea of theatrical metaphor. Using Miller’s own description in Timebends, discuss why he chose the 17 century setting rather than the 1950s. Ask them to think of a current event and what theatrical metaphor could be used to reinforce its themes and meaning. This could mean choosing a historic setting, as Miller did, or it might involve creating a visual metaphor, such as setting a current conflict in a boxing ring.

- The traditional gender roles of the characters can be frustrating for students, with Elizabeth perceived as a good but dull woman and Abigail, a classic ‘bad girl.’ From their research, what justifications can they provide for the female characters’ actions? What do they know about the restrictions on their lives and society’s expectations of their behaviour? An upcoming production of the play will have a female Proctor. What do they believe will be the advantages and disadvantages of this?

- Fake news: the rapid spreading of false stories and public shame are familiar to anyone with access to the internet. Ask the students to create a short piece of drama about someone who was accused of something and what they did to fight these accusations. Discuss how the themes of mass hysteria and honour continue to be relevant today.

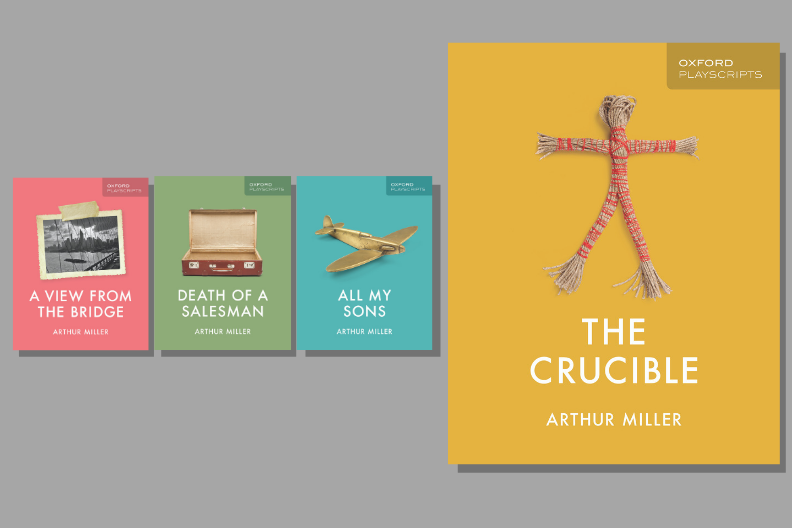

Oxford Playscripts: The Crucible. With the clearest and most accessible design, together with supporting activities, biography and contextual information targeting exactly the right level, this edition provides comprehensive, relevant and engaging support for students.