I’m on the “coronacoaster”: one minute I’m up and the next I’m down – it’s an emotional rollercoaster. Most of the time, I feel like it’s all fine and we are just in a new normal, but in the blink of an eye, I’m flying by the seat of my pants, heading down with the worry about the future. I’m hoping that my purchase of an antibody testing kit is my ticket off this hair-raising ride.

So, what is an antibody?

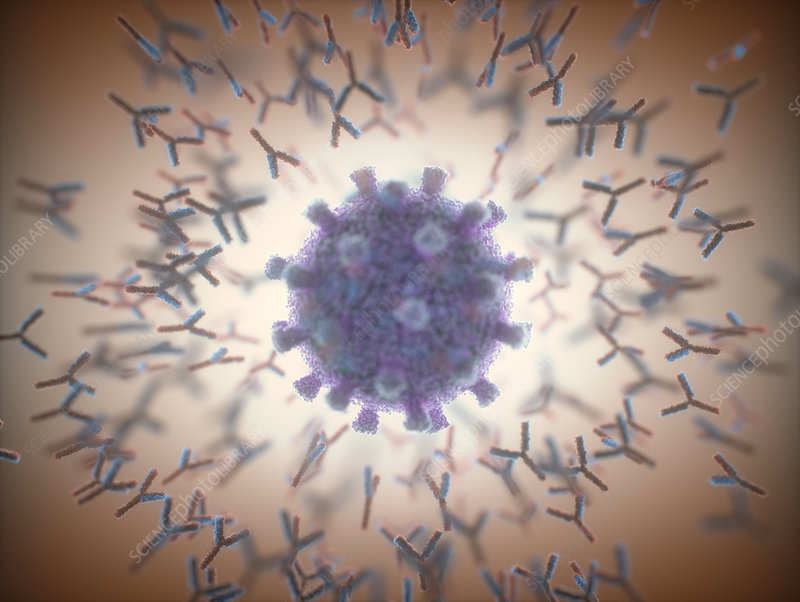

Antibodies are like the security guards of your body. They flow around in the blood stream and other body fluids, checking protein markers on cells and chemicals that they find along the way. If they manage to bind to any of these markers, they signal to the rest of the body that this is an antigen. This acts like a radio call from the security guard to base, issuing further response from the immune system.

But antibodies are specific, and only one type of antibody can be made by each, highly specialised, white blood cell. Apart from antibodies obtained before birth across the placenta, or in breast milk, most antibodies are made by the body in response to an unexpected or “non-self” protein marker. These immune response antibodies are part of our active immunity and are retained in small numbers post-infection, as memory cells. This ensures that, in most cases, the same infective agent cannot attack us again. Interestingly, allergic reactions are caused by this system malfunctioning and identifying a non-infective agent, such as pollen, as an antigen.

The role of plasma

B-lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, are activated to make antibodies. Blood is not a single substance, but a body tissue, made from specialised cells suspended in a straw-coloured solution known as plasma. You have probably seen your own plasma, as it is part of the liquid that fills blisters! Antibodies are found in plasma; they are made of long natural polymers called proteins. Therefore, if antibodies that match up to a specific infective agent are detected in blood plasma, it shows that at some point in the past, the person was infected with the agent.

Covid-19 testing

There are two types of tests for the Covid-19 illness:

- PCR, swab test – these test for presence of the virus SARS-CoV-2 and show that you have an active infection.

- Antibody (serology) test – uses a blood sample to test for antibodies which bind to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The test can only detect if the person has had an immune response to Covid-19 at least 14 days in the past.

In the UK, both types of testing are available, free of charge, to certain qualifying groups of people. But, as there is no treatment for Covid-19, and having antibodies present does not give any indication as to immunity, why is anyone getting tested?

Mass testing has been recommended by the World Health Organisation to give an important insight into understanding how the virus is spread and to be able to quantify the severity of the infection. This allows charities and governments to have an evidence-based approach to managing the pandemic. Having test data also allows health services to give the care that is needed. In addition, it allows them to track and trace people who may have been exposed and give advice to reduce the likelihood of the infection being passed on – this in turn reduces the all-important r-number.

The data that are emerging can be very worrying and, even though the disease is likely to be mild to moderate in most people, the death toll reported in the media can lead to anxiety. However, knowing that you have antibodies in your blood gives you the confidence that you have had the disease and, crucially, lived through it, which offers a level of peace of mind.

Home testing

A member of my household is in the vulnerable category. We are in week 11 of practising stringent social distancing. None of us have been ill during this time, so there has been no benefit to booking in for a PCR test. But, this year we have had a few episodes of a ‘nasty virus’; could this have been Covid-19?

I have been waiting eagerly for the antibody test as this could offer us some peace of mind. I was excited to learn of the government endorsement of the Roche and Abbott test, but we did not qualify for a free test; so I went ahead and purchased one for about £100.

It’s quite simple to order a kit on the internet, but I did a bit of research to ensure that it was one of the tests endorsed by our government. It came quickly, in an unmarked envelope that fit through my letter box. A blood sample was needed to send back to the lab. The test has not been guaranteed for this method of blood sample; it has only been certified for a qualified phlebotomist. But, quality checks suggest that the sample taken at home is likely to have a similar accuracy level and I thought this was still worth it.

The labelled sample is then sealed, put in a pre-paid envelope with a completed form and posted via a priority postbox to the processing lab. Then, the wait begins to get your results in a secure link sent via email.This where we are now.

How can we science teachers use the testing for coronavirus as a learning tool?

- As part of the Cells and also the Organisation topic in AQA GCSE Biology and AQA Trilogy, students need to be able to state the function and describe the adaptation for specialised cells. Students should also be able to explain why blood is a tissue.

- Students can prepare blood smears and interpret blood slides.

- As part of the Infection and Response topic in AQA GCSE Biology and AQA Trilogy, students need to understand how pathogens can be spread. We could use the idea of PPE for the medics taking and analysing the tests and discuss how this protects them from infection.

- The Working Scientifically strand of the curriculum lends itself to evaluating the risks and benefits of coronavirus testing.

What about me

And so, I’m back on the coronacoaster. Some people wonder if I test positive, will I behave like I’m superhuman, stop social distancing and go out and see people?… But that doesn’t sound like me. I hope that I am positive. This would give me reassurance that I had survived this disease once, and would therefore give me hope that should I need to, I could again.

And if I am negative? I won’t lie, my hopes are high that I have faced this deadly disease already and won the personal battle. If I don’t have the antibodies, I could persuade myself that the test wasn’t accurate, or that my blood cells are no longer making the antibodies. Otherwise, I must accept that I have yet to face this virus myself. I’ll cross that bridge when the results come in!

Sam Holyman is Second in Science at Aylesford School in Warwick, and formerly West Midlands ASE President. She is also author of a number of best-selling science textbooks for KS3 and GCSE, and a keen advocate of innovative teaching and learning.

She was nominated in the Teacher Scientist category for the Science Council’s 100 leading practicing scientists, is a Chartered Science Teacher, and has recently been awarded a CPD Quality mark.